In our CVAAS skype discussion last night one of our topics concerned how many atheists often focus on the religious idiot of the day.

There is a small-time preacher who is advocating making a list of all atheists for the purpose of discriminating against them. There is a small-time rabbi who claims that atheism leads to bestiality. There is a religious street preacher who is famous for baiting atheists and belittling anyone who explains evolution.

And atheist blogs tear into these people. They search out these people. They dig through the Internet and find posts that were made months ago and bring them out.

The comment that struck me during the skype discussion was to the effect that too many atheists are so focused on highlighting the problems with religious people that they are neglecting the mention of the benefits of living a rational life.

The comment that struck me during the skype discussion was to the effect that too many atheists are so focused on highlighting the problems with religious people that they are neglecting the mention of the benefits of living a rational life.

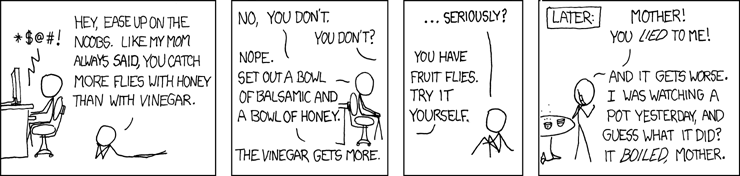

As the saying goes, "You catch more flies with honey...." (Well, it works in the saying...)

I am interested in increasing the number of rational thinkers in our society. Which leads to the question of "How"?

It has become painfully obvious that rational explanations, the scientific method, and evidence are often not enough to get a person to exchange a belief in pseudoscience and the supernatural for reality.

Sometimes ridicule of belief is enough to start a person toward change. As Christopher Hitchens has said, religion “should be treated with ridicule, hatred, and contempt". Sometimes this level of contempt is what it takes to get someone to realize that their beliefs are silly. When I was starting down the road toward atheism, a well placed jibe toward one of my beliefs made me angry enough that I examined that belief closely and was forced to the conclusion that the critical person was right.

But from what I can see, this seldom works, and it is too easy to mix up hatred of a belief with hatred of the person holding the belief. The criticism too easily becomes an "ad hominem" attack

"Love the sinner, hate the sin" is a phrase that comes to mind here.

Consider a person who has heard about a scientific discovery that deeply challenges her belief in divine creation—a new hominid, say, that confirms our evolutionary origins. What happens next, explains political scientist Charles Taber of Stony Brook University, is a subconscious negative response to the new information—and that response, in turn, guides the type of memories and associations formed in the conscious mind. "They retrieve thoughts that are consistent with their previous beliefs," says Taber, "and that will lead them to build an argument and challenge what they're hearing."

In other words, when we think we're reasoning, we may instead be rationalizing. Or to use an analogy offered by University of Virginia psychologist Jonathan Haidt: We may think we're being scientists, but we're actually being lawyers. Our "reasoning" is a means to a predetermined end—winning our "case"—and is shot through with biases.

Mooney writes that people become emotionally invested in a belief, and will defend that belief using something like fight-or-flight reflexes.

We're not driven only by emotions, of course—we also reason, deliberate. But reasoning comes later, works slower—and even then, it doesn't take place in an emotional vacuum. Rather, our quick-fire emotions can set us on a course of thinking that's highly biased, especially on topics we care a great deal about.

In other words, we are more likely to change our minds for emotional reasons, not for rational ones. We are said to "have a change of heart", not a change of mind.

So how do we apply this toward increasing the number of rational thinkers in our society?

It would seem that we need to get people to "have a change of heart" first, then teach them how to think more rationally.

But how do we do this?

The suggestion from last night was to focus on the positive aspects of a life lived rationally. Secular morality, and secular philosophy were mentioned. A life well lived.

We also discussed atheist celebrities. Many of these are much like Paris Hilton - they are famous for being famous (in atheist circles). Do they elevate atheism to a more visible position? Is higher visibility useful? These very atheist celebrities are often the same ones that tear into religious nobodies and who confuse ridicule of ridiculous beliefs with ridicule of religious believers. Pure vinegar.

Perhaps it is time that atheists start talking about the benefits of a rational life.

2 comments:

I think part of the problem in the modern Western (and Western-influenced) world is that, having been through the bottleneck of Christianity, we are culturally unaccustomed to thinking independently and flexibly about morality, philosophy, and the "life well-lived" as a coherent whole, as a way of life. For more than a thousand years, Christianity served as a complete system for society—morality, ethics, politics, science were all wrapped up in a convenient whole, which was hierarchically distributed. There was no need to think about the various parts of the system, and to do so could land a person in hot water for heresy. But during the last couple centuries, having shed the authoritative structure of the church and challenged the theological bases for its dictates, we have developed strong and relatively independent streams of morality, ethics, philosophy, politics, and science. There are a lot of good ideas, but they are splintered across many specialized disciplines. We have no means of coherence that is comparable to what Christianity provided.

In my experience, this splintering seems to be re-enacted every time somebody de-converts from Christianity and abandons theism. There is first a feeling of enormous freedom from having thrown off the shackles of authority. This is accompanied by huge disdain for the former oppressors. Then the new atheist finds others and enjoys a sense of camaraderie; attacking all those old theological bases for the dictates of Christianity becomes a sport. Meanwhile, the new atheist learns more about various moral philosophies, different ideas about politics, the wonderful achievements of science, and so on. But these are just pieces of what must still be a whole: living life as an individual in a society.

This is where atheists splinter (just like the rest of modern Western society) across political views, moral philosophies, ideas about science, and what it means to be an "atheist." Think about it long enough and it turns out to mean almost nothing, but that's not acceptable—since all of us who have thrown off the shackles of Christianity or Islam clearly need some binding factor. (You ever notice that the loudest atheists are former Christians and former Muslims? I'd guess it's because those are the two big religions that have been so successful with fundamentalism, of making assent to the factual content of various dogmas [i.e., intellectual shut-down] a central part of their way of living.) So we get weird ideas like "positive atheism," which is fine for a social club, but terrible if you're looking for a good, solid foundation for living. "Secular humanism" is much better (and, I note, is a product of the first half of the 20th century, when people just seemed to be more interested in thinking clearly about big, cohesive networks of ideas). But the right-wing public relations campaign against "secular humanism" has been so successful that it's not a label most people are interested in adopting. Also, the big secular humanist organizations, like CSH, seem (at least to me) beset with people who are not nearly so good at thinking about the big picture as their predecessors. Paul Kurtz is a brilliant guy, but I don't see anybody capable of succeeding him. We live in a world of small minds.

There's certainly room for disagreement, and I know a lot of atheists who would bristle at the suggestion, but I think people should look to Aristotle as a model. Here's a pre-Christian Greek who tried valiantly to tie everything into a single, cohesive view of the world. He even had some pretty good ideas about ethics. Unfortunately, he was also pre-science, so had no good ideas about systematic ways of building knowledge about the world.

[continued below]

[continued from above]

And I think one of the things that Aristotle got right was to recognize that living well is something we all want, but not something that comes easily or "naturally"—it takes skill and practice. That also happens to be just about the only good thing about most religions, in my view: they recognize the need for practice and they provide a structure for it. Atheism and secular humanism provide nothing like that. To the contrary, many atheists, having recently freed themselves from an authoritative system, are positively against this idea. (How many new atheists suddenly find themselves as new libertarians, too?) The ongoing focus on the church-and-state issue is not helpful, either. What we need is not to divorce politics from religion; we need to divorce supernaturalism from everything and then re-integrate politics back into moral philosophy, ethics, and science.

The trick with Aristotle is that the Catholic church used him, too, and look what happened to those nutters. They ended up ossifying into something that cannot abide the rapid developments of science. So if modern atheists are to take their cues from Aristotle, they would do well to learn some lessons from what the Catholic church did wrong.

In short, I guess, the big problem with atheists is that people who claim that label are frequently terrible at integrative thinking. And they spend way too much time (in my opinion) trying to tear things down. (Paraphrasing Jesus, "The irrational, gullible idiots we will always have with us.") Meanwhile, since they come, mostly, from religions that have degraded into mere authoritative systems for the distribution of dogmas, instead of training systems for lives well-lived, most atheists have no experience being in a system of practical training for a good life, and much less the ability to build such a system.

So I think there's much more to do than just talking about the benefits of a rational life. A society like ours, which seems to be falling apart, needs a broad, cohesive integration of everything. It's no coincidence, I think, that Aristotle came up with his big system in a world that had recently fallen apart, after the so-called Golden Age of Athens, in the fifth century B.C.E. And it's certainly no coincidence that Aristotle was co-opted by the Catholic church when he was rediscovered in the Middle Ages. In a confusing world that seems to be falling apart, people don't really need more iconoclasm and they need more than just a "rational life" to get them through it—they need ideas for how to make everything better.

Post a Comment